The UK economy is becoming increasingly parlous under the Labour Government, and a number of highly respected economists are forecasting a UK financial crisis in the next 12 to 24 months. This could see a sudden and sharp weakening of the pound and international investors demanding a higher return for holding UK government debt.

Is the negativity warranted? Probably. The 2024 budget has seen changes in tax policy prompt an exodus of high-income taxpayers whilst the labour government has written several big pay settlement cheques to appease unions. They have increased employment costs and shown a desire to nationalise some industries. Their expectation was that their policies would deliver economic growth and rising tax revenues, whereas the economic reality has been markedly different, with growth slowing and the budget deficit widening. The situation has been aggravated by Trump, who has elevated economic uncertainty through his tariff agenda, increased the cost of sales to America, and insisted that NATO members increase defence spending.

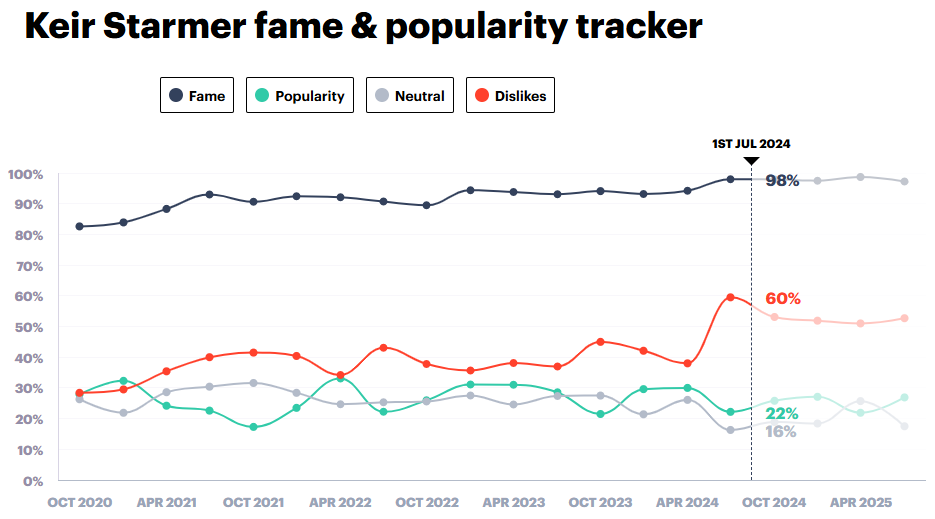

It seems clear that Rachel Reeves will find it difficult (impossible?) to balance the books and operate within her own fiscal rules. The choices faced are stark: increase taxes (unpopular), increase growth (difficult to achieve), reduce costs (unpopular), or adopt the ostrich pose and hope. There appears to be scant room to manoeuvre. YouGov political favourability ratings show that Keir Starmer’s popularity has collapsed since he was elected, with two-thirds of the public now holding an unfavourable view of him. There has also been rebellion within the Labour Party, which prompted the abandonment of proposed benefit cuts.

History is often a guide to (not a rule for) the future, and, in some ways, 2025 reminds me of 1976. The Labour government was running similar ideological tax policies targeting anyone deemed to possess wealth. At the time, Chancellor Dennis Healey famously boasted he would squeeze property speculators “until the pips squeak”.

The consequences of Labour’s economic policies in 1976 led to a buyer’s strike in the Gilt market and a spike in interest rates. The Bank of England had to raise interest rates from a low point of 9.5% to 15% and suffered the notoriety of issuing the highest ever coupon (15.5%) UK Government Gilt, which had a redemption yield of 15.65%. Things only improved after International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) officials were sent to bail Britain out. A secret meeting took place in London, where the cabinet initially rejected IMF proposals. However, it was forced to accept in December, after sterling had sunk from $2.02 at the beginning of the year to below $1.6. In return for its support, the IMF insisted upon cuts to public spending and increases in interest rates.

The collapse of the pound in 1976 was exasperated by a lack of foreign currency reserves that exposed the UK to a potentially catastrophic run on the pound. Is the situation any better today? Foreign investors hold over $2.8 trillion equivalent in UK Government Gilts, whilst the UK’s foreign exchange holdings amount to $117 billion. The ratio of 24 times does not leave me confident that the government could use foreign exchange reserves to defend a run on the pound.

This year, the Labour Government is faced with the same conundrum that it faced in 1976. Its current account does not balance. Ideologically, it wants to increase welfare obligations but is finding that increased taxes can’t keep pace with increases in government spending commitments. Those taxes also cover government debt interest, so if the debt grows at a faster rate than the ability to cover the interest on it, a financial crisis follows. During such a crisis, interest rates rise to reflect the growing risk, making the crisis worse – delivering a classic debt trap.

Do not despair, though – the UK is presently in a better financial position than it was in 1976, but it seems highly likely that the position will continue to deteriorate, so it needs to be carefully considered and monitored. Not only does the Labour Party lack the appetite to cut spending, but my feeling is that cutting spending in 2025 will prove more difficult than in 1976 due to the way the UK has evolved since then. The population is (on average) older, there are more pensioners, life expectancy has increased so pensions will need to be paid for longer, the pensions are unfunded, living standards have increased, and there is the benefit culture to contend with.

Britain is not alone with a budget imbalance and a government with socialist tendencies. If the unfunded welfare obligations of Britain lead to a financial crisis, it is unlikely to be the only G7 nation to suffer this fate.

It will still be possible to make money, but diversification will be even more important, and government bonds will no longer be the safe haven that the investment textbooks tell us they are. So, as an investor, what do you need to do?

- Keep calm. Remember that businesses and investors make money despite governments, not because of them.

- Ensure that you have appropriate currency diversification.

- Consider and possibly reduce your exposure to government debt.

- Contain duration. If an interest rate spike, occurs long-dated bonds may suffer.

- Consider alternative assets and asset classes that are not highly correlated to currency or interest rate movements.

As always, if you’d like to speak to us about your investments, please don’t hesitate to contact us and one of the team will be happy to help.