ING published an interesting note last week suggesting that there are such things as ‘good’ interest rate cuts and ‘bad’ ones. They went on to suggest that a ‘good’ interest rate cut would be characterised by falling inflation meaning that the central bank concerned has room to cut rates. By contrast, a ‘bad’ interest rate cut is sanctioned because the economy is in dire trouble.

Whilst the US and UK central banks both left rates on hold last week, both committees suggested that despite inflationary fears, the next move in rates would be down.

Perhaps the key quote from the US Federal Reserve’s (“Fed”) statement was that ‘someone has to pay’. Despite three months of favourable inflation data in the US, the expectation is that the inflationary impact of tariffs will be felt later in the year. Of course, the exact economic impact of tariffs on the US is unknown and there is little historical data to help suggest an answer.

However, the Fed signalled little urgency to cut rates. Despite the exultation of President Trump to cut rates, the committee appears committed to a ‘wait and see’ policy. Potentially rising inflation and slowing growth is a difficult situation for the Fed to deal with and on current evidence the committee members are only expecting to be able to cut rates modestly this year and certainly nowhere near the immediate 2.5% cut that President Trump favours.

Closer to home the Bank of England’s MPC committee also left rates on hold last week. The vote was 6:3 with one member moving from no change to voting to cut.

The minutes reveal that the committee was expecting wage growth to ‘slow considerably’ during the rest of the year. This is attributed to a cooling labour market. The MPC left its core guidance in place that any rate cuts will be ‘gradual and careful’.

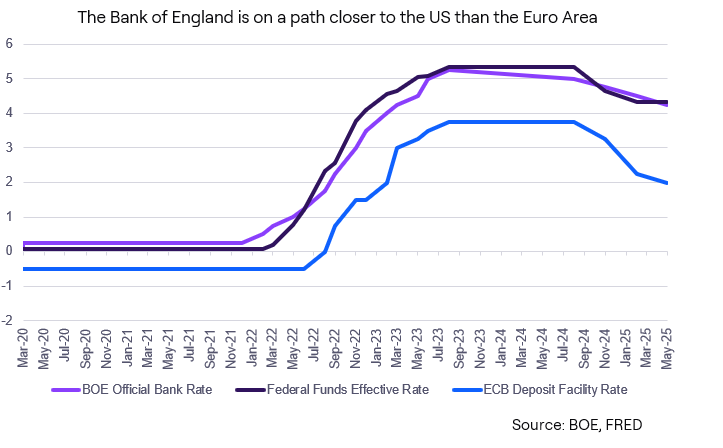

Markets are now factoring in an 80% chance of a rate cut in August, with perhaps another cut in the Autumn. The profile for both the US and UK rate movements look similar as the graph below shows, albeit perhaps for slightly different reasons.

Of course, the current geopolitical situation continues to add to the uncertainty. The impact of the tensions in the Middle East remains first and foremost a humanitarian crisis but the economic consequences remain huge. One obvious impact is that the price of oil is now $10 a barrel higher than it was a month ago. Whilst this has the potential to be inflationary, current prices are below recent highs and the key will be whether higher prices are sustained. This of course is further influenced by whether tensions remain high and whether threats to supply become real.

But to return to the first point in this note, falling inflation would tend to suggest that planned interest rate cuts may fall into the ‘good’ category whereas economic damage caused by high oil prices and geopolitical tensions could be considered a catalyst for ‘bad’ cuts.