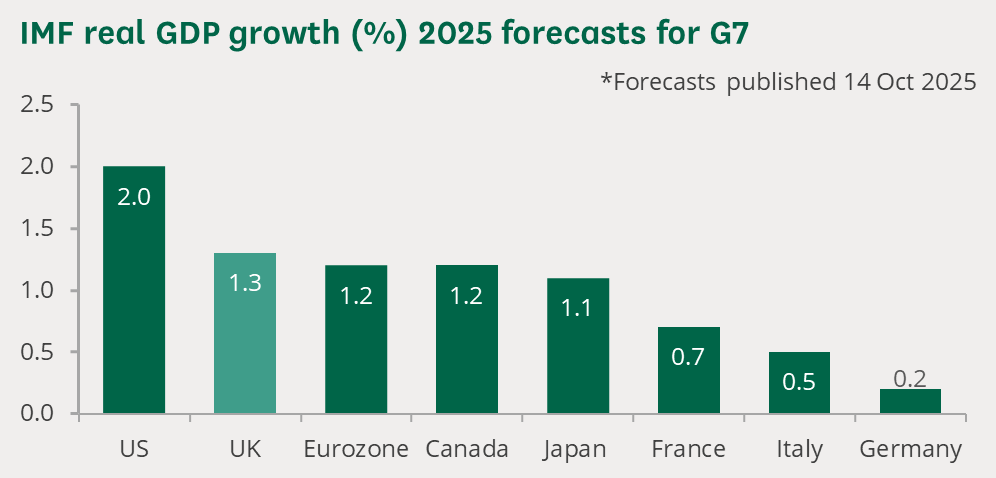

The International Monetary Fund released its latest round of forecasts last week. Rather surprisingly, given the amount of doom and gloom in the press, it predicts that the UK will achieve the second highest rate of growth amongst the G7 countries this year. Whilst this is a reasonably positive headline, the actual predicted level of GDP growth is only 1.3% (perhaps the comparative return is better than the actual predicted return).

Central bankers on both sides of the Atlantic have also been talking this week ahead of the next round of official interest rate decisions.

The US Federal Reserve (“Fed”) will next meet on 29th October, and markets are expecting another 25-basis point cut. At the moment, in the US it appears that the weakening jobs market is the main concern over inflation fears. This is probably sufficient for the Fed to act in October and perhaps in December, but the outlook for 2026 is less clear. Whilst the US jobs market is giving cause for concern, the economy is proving reasonably resilient. To go back to the graph above, the US is forecast to be the best performing of the G7 countries this year. It could, therefore, be that ultimately market expectations of further cuts in bank rates in 2026 are curtailed by a combination of resilient economic growth and above-target inflation.

There are, of course, a number of unknowns for the Fed in 2026. These really revolve around the interaction between the government and Fed. President Trump is on record as supporting lower interest rates and is agitating to influence the composition of the rate setting committee to better reflect his position. In addition, Fed chair Jerome Powell will finish his term of office in May 2026. His successor has not been announced yet, but this is another opportunity for the President to pursue his own agenda.

Closer to home, the next UK interest rate decision is on 6th November. Markets are currently expecting that rates will remain unchanged at 4% for the remainder of the year with further cuts in 2026 but, similarly to the US, above-target inflation coupled with anaemic growth complicates the situation. The Bank of England’s ("BoE") Chief Economist, Huw Pill, advised that The Monetary Policy Committee ("MPC") should take a ‘more cautious approach’ to lowering interest rates. He went on to warn about the “need to recognise that the stubbornness of inflationary pressures is becoming more pressing”.

The latest UK inflation data will be released next week, and some forecasters are expecting the figure to come in at 4% - double the BoE’s target. Worryingly for the MPC, household expectations of future inflation rates are also rising, which has the potential to ignite a price/wage spiral. Other MPC members appear more concerned about lower growth than higher inflation.

Overall, both the UK and US are in similar positions with positive GDP, albeit at the lower end of expectations, but stubborn above-target inflation. It could be that this situation remains for some time, but the longer inflation is above target, the greater the danger that higher future inflation expectations become ingrained in the wider economies.

For this reason, it could be that markets are expecting too many interest rate cuts in 2026 and that official interest rates, like inflation, remain stubbornly higher.