Key highlights:

- UK economic performance has sharply declined since Brexit, with GDP growth, productivity and UK equities lagging other major economies.

- Mounting risks include high inflation, rising debt, twin deficits (trade & fiscal), weak productivity, shrinking workforce, ageing population, and high energy costs.

- Current fiscal policy is unsustainable, with a rigid goal to balance the budget by 2029 seen as unrealistic and economically damaging.

- There are historical parallels to past crises such as the 1976 IMF bailout, Black Wednesday, and the 2022 Liz Truss mini-budget collapse.

- Pressure is building on the government ahead of the November budget, likely forcing a policy U-turn or risking a financial crisis.

- Potential solutions include bold pro-growth reforms such as deregulation, tax system overhaul, workforce expansion via skilled immigration, energy policy reset, and global trade re-engagement.

- It’s not all bad news – any crisis could bring opportunity but decisive policy shifts will be needed to restore growth, improve investor confidence and unlock value in UK assets.

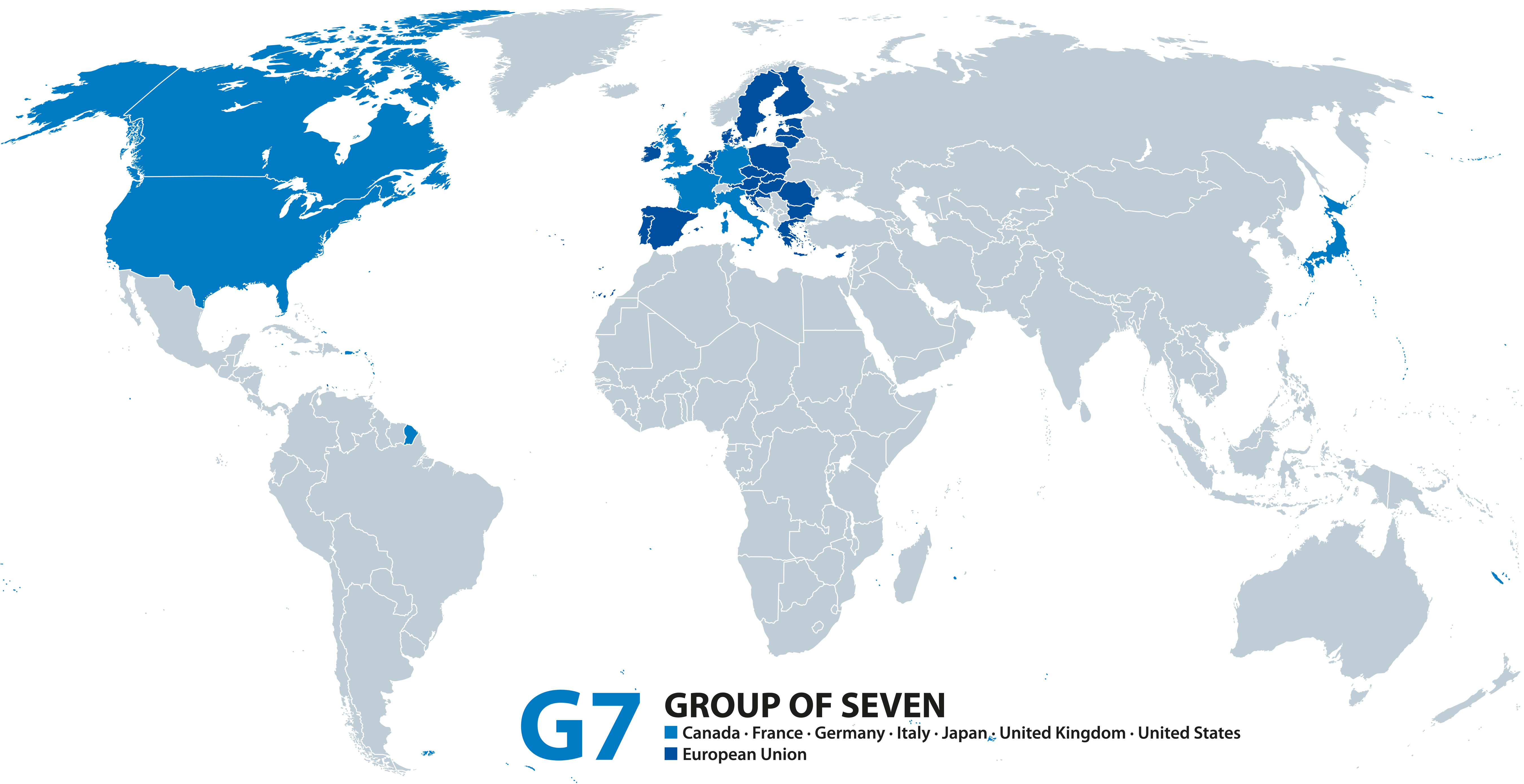

For the 25 years preceding 2016, Britain experienced a period of strong per-capita GDP growth and was one of the best-performing economies in the G7. Since the Brexit vote in 2016, this has reversed – the UK economy has significantly underperformed compared to most other developed economies and UK equities have lagged every other major stock market by a wide margin. Even UK institutions currently hold minimal weightings in UK stocks.

There is a growing view amongst economists and commentators that the UK is heading for a financial or economic crisis due to a number of problems. These include a long-term decline in economic growth, high inflation and the stagflation backdrop, rising public sector debt, growing twin deficits (trade and fiscal), weak and declining productivity, a shrinking workforce, an ageing demographic, excessively high energy prices and a widening gap between government spending and revenue generation. The fracturing world and rising geopolitical risks add to the challenges the UK faces since the government also has to address issues such as rising income and wealth inequality, increased spending on defence, global trade frictions, energy and food security and climate change.

The UK has a history of economic crises

I can remember three previous UK economic crises, although the first one in 1976, when the government had to borrow from the International Monetary Fund, is a little vague in my memory. I remember the second one very well, as I had started my career in wealth management and was managing several multi-manager funds at the time. “Black Wednesday”, on 16th September 1992, was the day when the British Government was forced by markets and currency speculators (including George Soros) to abandon its entire economic framework and the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (“ERM”) crisis followed. This framework had, at its core, the flawed objective that the Pound should be pegged against the German Mark at a rate of 2.95 and that monetary and economic policy should be managed to keep this rate within a 6% range on either side.

When Germany raised interest rates in the early 1990s to counter the inflationary impact of German reunification, this caused significant stress across the whole of the ERM and resulted in the Pound falling heavily against the German Mark. Initially, the Bank of England responded with a series of currency interventions and rate hikes, but when this failed to stem the tide, the Government announced that the UK would leave the ERM. Beyond the market chaos that followed, the longer-term result was something that few imagined possible: a generational period of economic outperformance unmatched in Britain since the Industrial Revolution of the early 19th century.

The Liz Truss crisis in October 2022, whereby the Government outlined an economic U-turn based on a “go for growth” strategy, was the final and most recent crash, although this was, of course, very short-lived and ended in the shortest tenure of any British Prime Minister.

In a similar way to the fixation on a pegged exchange rate within the ERM, the Starmer government (and, in fairness, the preceding Conservative government) has become fixated on a flawed and unachievable economic objective, namely a “non-negotiable” commitment to balance the public sector’s current budget beginning in the financial year starting April 2029. This target is both out of the government’s control and irrelevant to the current economic reality. As investors, businesses, consumers and voters begin to understand the contradiction between the political rigidity of this policy and its economic impossibility, the credibility of all government decisions and announcements is rapidly eroding. This is resulting in further economic deterioration, making the objective increasingly less achievable and creating a downward spiral of economic, political and financial decline.

The pressures on the government are building

The pressures are building on the government to change tack for several reasons: higher-than-expected interest rates and Gilt yields, rising defence spending, the politically driven abandonment of welfare reform, ongoing public sector spending increases and disappointing revenues from “tax tinkering” changes. It’s also clear that the economic data is highlighting a toxic mix of faltering growth, persistent inflation and growing budget deficits that make the fiscal targets unattainable. It doesn’t help the government’s case that Germany has joined most other G7 economies in removing its fiscal brake, leaving Britain as the only major economy still shackled by arbitrary and completely unworkable fiscal rules.

Whilst a catalyst may be needed to force the government into a policy U-turn and abandon its fiscal restraint, the pressure is building and the annual budget due in November will force the government to face a very stark choice. Chancellor Rachel Reeves will either need to propose intolerable tax increases and/or significant spending cuts, all of which would crush any hopes of reviving growth and prove politically unviable. The result could spark a financial crisis and force a Black Wednesday-style abandonment of the government’s fiscal straitjacket. Of course, it is possible, though unlikely, that the Chancellor pre-empts the chaos by unveiling a new economic framework that is genuinely capable of reversing the miserable decline of the UK economy and initiating a rosier long-term outlook for growth, public finances and per capita wealth.

It’s not all bad news

The good news is that whether the government changes course voluntarily or is forced to by markets and a crisis, there are potential solutions available, and the UK could soon be facing a brighter future. The policy changes required to stabilise public finances, restart growth and reverse the decline in the UK’s relative economic standing are bold and transformational but not impossible. Just like the reforms that followed the ERM crisis, they need not prove unpopular in the long run, even if they seem controversial or embarrassing in the short term. Indeed, the government has a great opportunity to embark on a strategy of significant economic and policy reform, which in turn would help to make the UK investable once again and present some very attractive investment opportunities.

In my view, the government needs to learn from the “go for growth” strategies currently pursued by Germany, the US, Japan and China. It needs to do everything it can to attract more inward and domestic investment in order to generate higher nominal and real growth. This would include an end to its current policy of fiscal restraint, deregulation and slashing red tape/bureaucracy, infrastructure investment to boost connectivity and productivity, finding ways to expand the workforce through higher participation rates and skilled immigration and a significant reduction in public sector spending.

In addition, the government needs to reverse its crazy energy policy (again, like Germany), which is resulting in a considerably higher cost of energy compared to many other developed (and developing) economies, and remember that economic activity is simply the conversion of energy. Any country that has access to cheap and plentiful energy has a natural advantage. Also, a complete overhaul and reform of the tax system is required. Although it’s true that the UK tax take has risen materially over the past three decades, it remains relatively low compared to many other advanced economies. However, successive governments have reduced the tax burden on average workers and replaced it with increasingly complex and “stealth” tax mechanisms aimed at maximising taxes from a base that is too narrow, rendering the strategy unworkable, ineffective, unfair and anti-growth.

Finally, the government needs a trade and growth policy that is focused on doing business and attracting investment from as many global partners as possible, which certainly includes the US and China as well as getting closer to Europe again.

Strong leadership is required

As well as the very challenging economic environment, the political system also makes it difficult for any government to achieve what is required and it would likely require a “Trump” or “Thatcher” style reformer to take the required action. The Bank of England (“BoE”) would also need to play its part to help manage the economic and financial risks. In the event of a crisis, it would need to use all levers available, including interest rates, quantitative easing, liquidity and reserve management, to support growth and prevent a financial or banking crisis. Longer-term, the BoE would need to follow the path of the Federal Reserve and tolerate higher but controlled inflation in order to achieve higher nominal growth. It would also need to continue financial repression to help keep Gilt yields and financing costs at manageable levels.

At some point over the next year or so, the government will likely need to act aggressively to either avoid a crisis or deal with the likely consequences of one. We may well see a significantly weaker Sterling, higher Gilt yields and weaker UK stock markets as a result. However, such a crisis together with a strong policy response could dramatically improve the long-term economic and financial outlook for the UK and provide a number of very attractive investment opportunities for both domestic and international investors. This may finally be the catalyst to unlock some of the undoubted value that is present in UK stocks today.