The question of the sustainability of the debt loads of Western governments is an interesting topic. It is a widely accepted problem; however, it is often largely ignored except in moments of panic, as we saw with the infamous UK “mini budget” in September 2022. So, with the issue rearing its head again in the last week, we thought now might be a good time to share our thoughts on the issue and, crucially, how we think people should think about it when considering their money.

How bad is it?

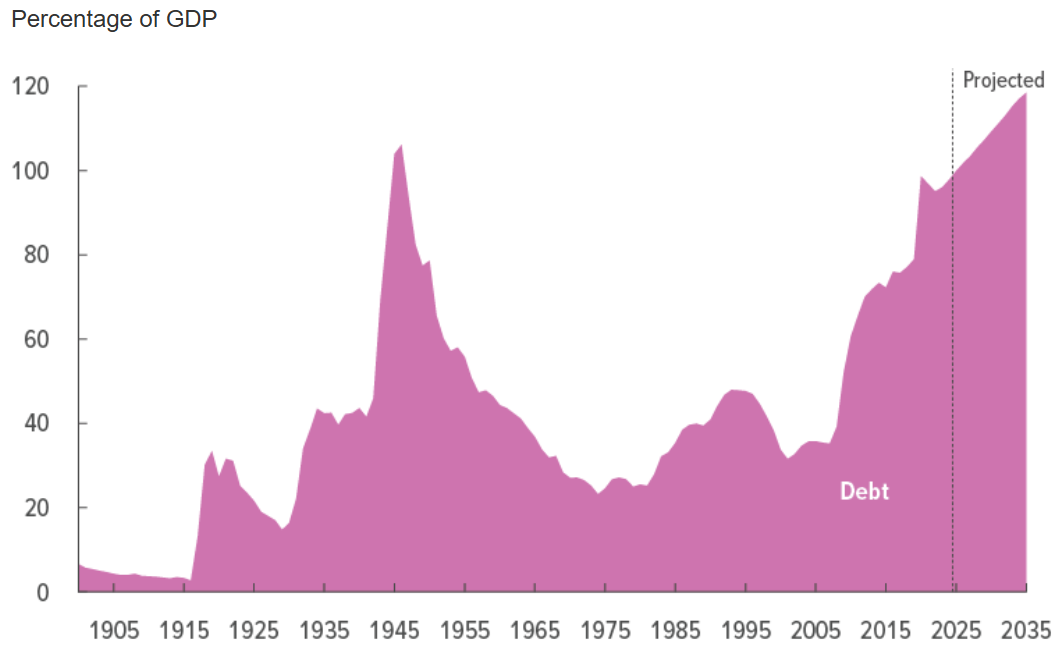

Government debt levels in the western world are undeniably high and rising. Depending on how you measure it, US government debt is now around the level last seen at the peak of World War II and is set to rise further from here.

It is hard to get your head around the sheer scale of the debt. In nominal terms, for example, US government debt was around $20 trillion a decade ago. Today, it has almost doubled to roughly $37 trillion (if you want a bit of ‘fun’, you can watch the US borrow $1 million in real time here – worryingly, it only takes about 20 seconds).

How did we get into this position?

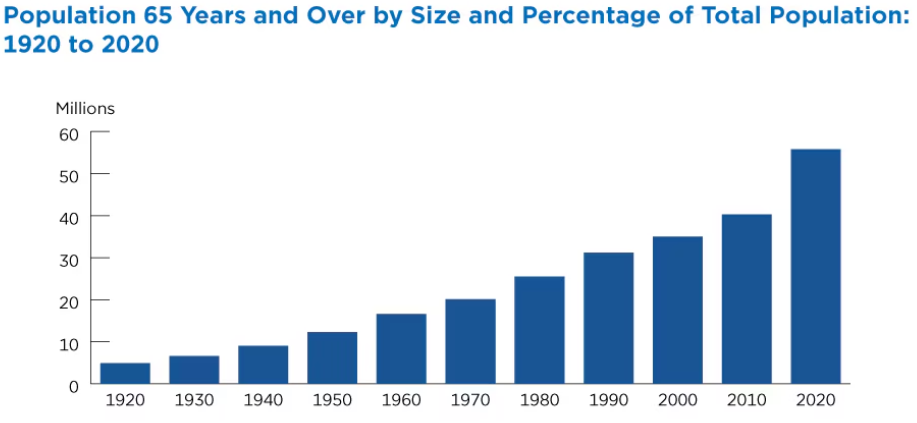

As tempting as it might be to blame dysfunctional politics, the root cause of the debt piles is more structural than that. Our populations are aging, and as working age populations shrink and retired populations grow (increasing the dependency ratio) tax take falls and spending on care rises.

Retired people pay less tax and draw more from the state in terms of health and social care costs. While many have earned this right through years of paying taxes, the reality is that current taxpayers must foot the bill, as there is no accrued pot of savings from past taxes to cover these costs. This ratio of taxpayers to dependants has, however, materially shifted over recent years. Today, one in every six people in the US is over 65, according to data from the US Census Bureau, up from one in 20 100 years ago.

This is an unavoidable fact, but, while this major issue is plain for all to see, it is generally seen as a “tomorrow problem” and therefore attracts relatively little attention in either the national conversation or even in market circles. This is, however, starting to shift and we have seen it come to the fore several times in recent years.

Part of the reason for the shift is the rise in interest rates. While the effect takes time to work through, the major rise in global interest rates we saw in 2022 means the average interest rate, the US government pays on its debt has risen from around 1.6% in early 2022 to over 3% today, according to data from the Peterson Institute. This doubling of the debt load, combined with a doubling of the interest rate, means the sustainability of debt in Western nations, such as the US, has deteriorated rapidly in recent years. The House Budget Committee, in a piece entitled “Sounding the alarm”, recently noted that within the next decade, for every dollar the US borrows, half will be spent on interest payments on existing debt.

That is a tight financial spot to be in, and dysfunctional politics makes taking the politically unpopular decisions required to address these issues much harder. While I am using the US as the poster child of this issue, it is not a position that is unique to the US. Other countries, such as the UK and Japan, are in similar positions, albeit to differing degrees.

It is this rising pressure on government finances that has caused moments of political stress in recent years, be they UK budgets, French elections or US debt ceiling debates. To bring the issue to the top of the agenda (albeit briefly so far) and to trigger concern and market volatility as a result.

Are governments going to default?

In short, no. In the traditional sense, governments such as the UK and US, that borrow in a currency that they control, are very unlikely to default in the traditional sense. They can raise taxes, influence interest rates and ultimately print money if they need to. This doesn’t, however, mean that debt is a non-issue or that lenders to western governments are guaranteed to get a good return on their investments.

So, what could happen?

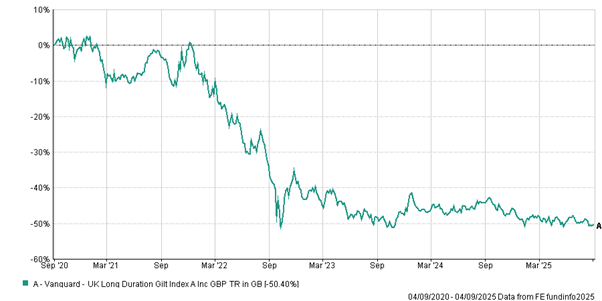

Worries over debt can trigger short-term market volatility, as we have seen; however, most assets will ultimately recover from such events given time. The areas of stress that we worry about are long-dated government bonds and their associated currencies. While governments can keep short-dated bond yields under control fairly easily, the longer-dated bonds, with their more volatile prices, are more at risk. For example, the five-year total return of the Vanguard U.K. Long Duration Gilt Index Fund can be seen below. Looking forward, with a yield of 5.3% on this portfolio today, a repeat of the below seems less likely, however, it is a good example of the risks that are bubbling along under the surface. And even at higher yields, the price of these types of assets could well continue to be volatile.

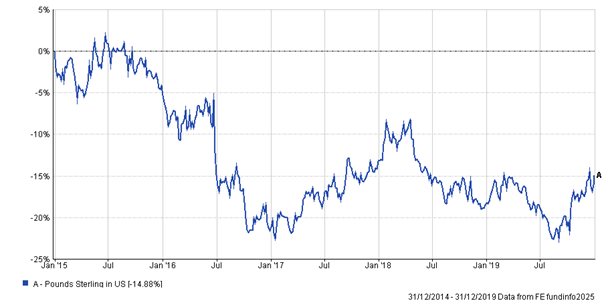

Looking forward, it is currencies that look particularly vulnerable to us today. The dollar, for example, has been notably volatile since the election of Donald Trump last year, losing around 7% versus the euro. Devaluations on the lines of the pound over the Brexit period may be worth bearing in mind when looking forward. Over that period, the pound lost as much as 28% versus the dollar and has stayed materially weaker level ever since. With geopolitical situations as they are, we wouldn’t rule out further devaluations in the pound or other Western currencies over the next few years.

History has shown us that by far the most common way for over indebted governments to resolve their debt issues is to debase their currencies. Be that through reducing the silver content of coins in the late Roman empire or the corrosive effects of inflation or money printing (quantitative easing) in the modern world.

So, what should investors do about it?

- Be wary of the comfort blanket of cash. While cash in the bank paying a couple of percent in interest with no fluctuation in capital value might seem like a cosy place to be, and can be a great tool if you plan to spend the money in the next 12 months, if you hang on to low returning assets for any length of time, you may find the money buys you less in the future than it did when you squirreled it away.

- Watch out for regional/currency exposures. With politics driving market volatility and currencies being a potential pressure release valve, the chances of big swings at a regional level remain elevated. In that type of environment, making sure you don’t have any excessive or unintended regional or currency exposures could avoid some nasty surprises in the future.

- A sensibly managed portfolio should still be fine. The good news is that a well-diversified and actively managed portfolio should continue to do its job. In our portfolios, we hedge out currency exposure on our bond allocations and carefully manage our regional/currency diversification on the equity side. We also work to ensure that our lower risk assets are paying us a rate of return that should keep pace with prices and over time, quality equities should provide real returns to help defend the overall purchasing power of your money.

- If you want to go further, consider gold. If you have a strong view that the above issues are likely to be key in the coming years, an asset to seriously consider is gold. The caveat is that the gold price is volatile, has had a strong run of late and can spend multiple years trading sideways to down. In the long term, however, gold has a long history of holding its purchasing power, and if geopolitical tensions and currency debasement persist, it may well have its moment to shine. Given its unpredictability in the short term however, it is something of a personal choice about if or how much gold you want in your portfolio.

In short, and going back to the title of this article, while the prospect of Western governments outright defaulting on their debts remains highly unlikely, investors should be aware that the real risks lie in subtler forms of default through persistent inflation and currency depreciation, which will erode the purchasing power of both cash and fixed-income assets over time.

The key is to stay diversified and avoid taking on unnecessary risks. Holding too much cash can be costly if it loses purchasing power, and large, unhedged currency exposures can create unwelcome surprises. A well-balanced, carefully managed portfolio should remain well positioned to withstand these challenges.